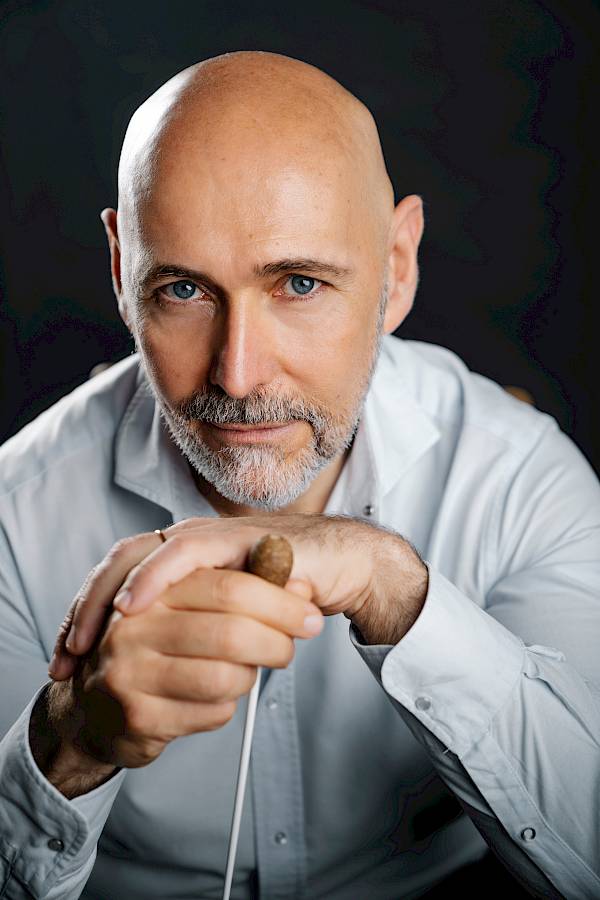

Im Gespräch mit dem Dirigenten Enrico Onofri

What inspired you to bring together works by Sammartini, Boccherini, and the young Mozart for this concert?

Their joyful, lively spirit seemed perfect for an Advent concert. This is apparently not the case with Boccherini’s symphony, a work the Italian-Spanish composer wrote inspired by the Sturm und Drang movement that was rapidly spreading across central and northern Europe. The symphony is therefore characterised by a dramatic writing style, with the sole exception of the central movement: a pastoral “Lentarello” that perfectly captures the Christmas atmosphere of southern Europe, accompanied by the calm and merry sound of bagpipes. In addition, Mozart’s Symphony No. 29 represents one of the turning points in his symphonic writing, and I consider this piece a true gift to humanity.

Mozart composed his Symphony in G major at the age of fourteen. What strikes you most about his musical voice at this early stage?

This small symphony, composed between childhood and adolescence (and therefore perfect for an Advent concert, since the presence of a childlike spirit cannot be missing in a pre-Christmas celebration), is in my opinion Mozart's first symphonic masterpiece, in which the move away from the influence of his father Leopold is already clear. It is a gem both in terms of form and thematic material, and although it is marked by the Milanese gallant style – the symphony is one of the works connected to his visit to Milan in 1770 and his close relationship with the local composer Sammartini – we can already recognise the Mozart of the future. For example, some hints of the “Turkish” style can be found in the last movement, which would then be fully developed in the 1770s and 1780s in the finales of the Violin Concerto K. 219, the Piano Sonata K. 331, and of course “Die Entführung aus dem Serail”.

As a specialist in historical performance practice, how do you balance authenticity with the expectations of today’s audiences?

Authenticity has always been a chimera in music, because every piece of information that comes to us from the past must be realised through our modern experience and the different personalities of musicians. This inevitably means using the tools at our disposal to bring each piece of information to life. There is no doubt that we should strive to get as close as possible to what the sources suggest, but there are differing opinions on how to do so: each interpretation is therefore always, and only, a hypothesis. In this regard, HIP (Historical Performance Practice) has, for years, reached a stalemate, where the standardisation of performances has replaced the keen and curious spirit of investigation that once characterised it. Today, in my opinion, the only meaningful work we can do is to find a balance between what historical sources tell us and our modern sensibilities, avoiding facile extravagances or crossovers, but approaching the music with strength of heart and mind, guided by a renewed spirit of ongoing research. Music is language, and this is precisely what historical sources (if we wish to reduce their complexity to a single principle) ask of us: to ensure that music speaks to the listener’s soul. We cannot escape filtering it through our modern perspective as interpreters, yet a solid foundation of knowledge and a clear vision of what the score can powerfully convey help us achieve that restless, delicate balance. For this reason, I prefer to define HIP as a more human, and perhaps more honest, Historically “Inspired” Performance.

Is there a piece in this concert that holds special personal meaning for you? If so, why?

They all are, for the reasons I have explained. However, if I may say so, the pastoral movement in Boccherini's symphony strikes a special chord, as it reminds me of my childhood when shepherds from the Abruzzo region still descended from the mountains with their bagpipes into the streets of cities across Italy, loudly yet tenderly playing our traditional Christmas melodies. A tradition that has now disappeared but whose sound — made of reeds and sheepskin — carries the scent of a lost past.